China’s Automotive Slowdown: Tesla And The EV Startups (NASDAQ:TSLA)

Xiaolu Chu

Introduction

The sales year started off with a whimper. First, the covid stimulus package for the auto industry – a cut from June 1-Dec 31 of the car sales tax from 10{515baef3fee8ea94d67a98a2b336e0215adf67d225b0e21a4f5c9b13e8fbd502} to 5{515baef3fee8ea94d67a98a2b336e0215adf67d225b0e21a4f5c9b13e8fbd502} – expired. Those planning to buy cars in early 2023 instead made their purchases last year. In addition, the Chinese central government has been winding down its incentives for New Energy Vehicles (NEVs) for several years. They, too, expired at the end of 2022. That pulled planned NEV sales from 2023 into 2022, over and above the impact of the covid tax cut. In other words, electric vehicle (“EV”) sales in late 2022 were artificially high. This year will be grim across the board for the China automotive sector.

Local government incentives aren’t picking up the slack. Beijing has capped its 2023 NEV license plate incentives at the 2022 level of 70K units, while for 2023 Shanghai eliminated free license plates for PHEVs (and refuses to license urban commuter EVs such as the GM Wuling Hongguang Mini). Now Hunan has begun a 元5000 cash-for-clunkers subsidy, and the central government is urging local governments to upgrade their fleets from ICEs to EVs. However, more prosperous localities such as Shenzhen have already completed the switchover to EV taxis and buses. Most regional and lower-tier cities face a budget crunch, so the process will be slow and will focus on low-priced vehicles. That’s bad news for the many NEV startups, and for Tesla, Inc. (NASDAQ:TSLA) which sit in the premium segment.

Analysis is complicated by the Chinese [lunar] New Year holiday in late January. China is now an urban society, but its cities are populated by workers who migrated from rural areas. This year, around 250 million people traveled back to their hometowns. Car dealerships were closed, and those that reopened early remained empty. Of course, the government offices that issue license plates were closed, too.

To reiterate, it’s payback time. January sales fell 35{515baef3fee8ea94d67a98a2b336e0215adf67d225b0e21a4f5c9b13e8fbd502} overall, and 28{515baef3fee8ea94d67a98a2b336e0215adf67d225b0e21a4f5c9b13e8fbd502} for battery EVs (“BEVs”). However, as I outline below, February sales looked good only in comparison to January. That is bad news for Tesla, which will face lower margins and higher costs, due to lower capacity utilization and the delayed feed-through of higher commodity prices. It is worse news for the many startups, which will see poor sales from now until the normal cyclical increase that starts in September. NEVs are also facing pricing pressures, due to the multitude of players and spearheaded by Tesla’s price cuts.

Additional months of negative cash flow are very bad news. Already, Weltmeister (not traded) has effectively gone out of business, selling no cars this year and closing most of its remaining facilities last week. In their latest financial statements, available on Seeking Alpha, operating income remained negative for Li Auto, Inc. (LI) [Dec 2022], XPeng Inc. (XPEV) [Sep 2022], and NIO Inc. (NIO) [Dec 2022]. Sales of other entrants – Neta, Zeekr and others (not traded) – remain at very low levels. Again, BYD is an exception, as is GAC with its Aion brand. Both are profitable (or are part of larger, profitable enterprises), and so face no immediate pressures. They (alongside Tesla) also happen to be the two largest and best-performing NEV players.

Below I look at overall passenger vehicle sales, and then turn to NEVs. Going into 2023 Chinese analysts were already looking at lower growth, of the order of 30{515baef3fee8ea94d67a98a2b336e0215adf67d225b0e21a4f5c9b13e8fbd502}. I believe that is optimistic in terms of unit sales, and will represent minimal growth in 2023 for revenue and a negative for cash flow. I don’t attempt projections, since there are many articles on Seeking Alpha to provide a baseline. My last section focuses on Tesla, reiterating my January 2022 SA article projecting that Model 3 sales would decline.

Note that my core datasets are for retail sales of light passenger vehicles, but do not include imports. They also do not cover light commercial vehicles or buses, and are not wholesale shipments so ignore exports.

Payback: Overall Vehicle Sales

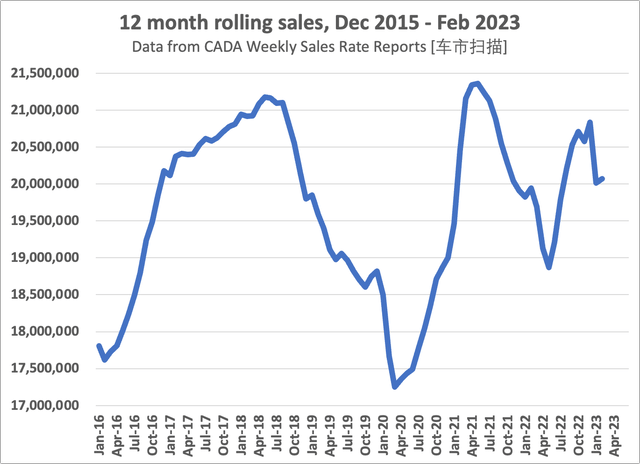

First, China remains the largest vehicle market, surpassing both Europe and North America. But it’s not growing. The migration for towns and farms to cities has ceased, consumers are under pressure as growth remains slow and real estate prices continue to fall, and the working-age population has been falling for a decade. Sales peaked in 2017, and will not expand going forward.

Author’s database, compiled from China Auto Dealers Assoc reports

What are the prospects for CY2023? The government is hoping for 5{515baef3fee8ea94d67a98a2b336e0215adf67d225b0e21a4f5c9b13e8fbd502} growth, but is looking to achieve that through pushing banks to lend for infrastructure and real estate investment. To use a monetary policy aphorism, that’s pushing on a wet string. Local governments saw their fiscal position deteriorate the past two years, and now have bills to pay for the covid testing mandated (but not paid for) by the central government under last year’s rolling lockdowns.

I spent most of my career as a specialist on Japan’s economy, and was in Tokyo in 1992 when their real estate bubble burst, and worked for a Japanese bank before graduate school. I’ve spent days in seminars looking at the evergreening of bad real estate loans, and how that undermined the effectiveness of macro policy. China is going down the same route, in part because that’s the only policy tool Beijing has, given the already complete buildout of regional airports, high speed rail and, lest we forget, a national expressway system that is more extensive than those of the U.S. or Europe – and doesn’t yet need maintenance.

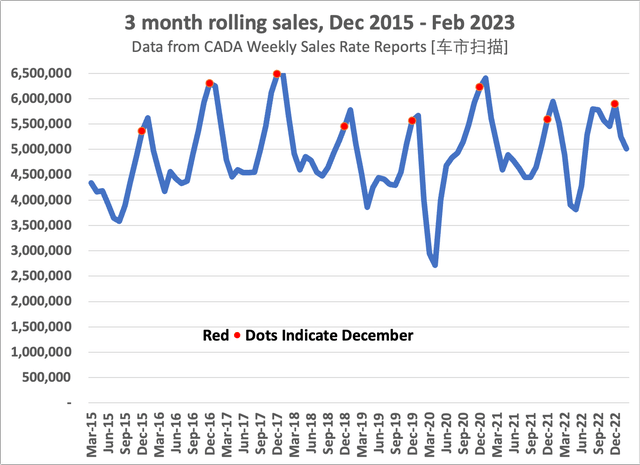

Let’s return to automotive, and look in more detail at passenger vehicle sales. The graph below provides sales using a 3-month moving average. To help with interpretation, December each year is marked with a red dot. First, sales show a distinct seasonal pattern, peaking at the end of winter, in January when the New Year falls later in February, and otherwise (as this winter) in December. Sales then fall through August, in some years with a June bump, before beginning their annual fall ascent.

However, 2022 was different from the previous 7 years, with the rolling average showing an early August peak. That difference represents roughly 700,000 extra sales, sales that will not be booked in the first half of 2023. Compared to recent years, that suggests that sales through July will be down 10{515baef3fee8ea94d67a98a2b336e0215adf67d225b0e21a4f5c9b13e8fbd502}, assuming that consumers will be spending as normal. The Chinese government doesn’t believe that will be the case, accepting lower growth and instead focusing on financial system stability. (See, amongst many possible examples, “Caixin Global, Mar 8, 2023: China’s Financial Shake-Up Shows Policymakers’ Growing Focus on Stability, Risk.”) For the sake of brevity, I won’t examine other indicators, such as commercial vehicle sales. All point in the same direction.

Authors database, compiled from monthly CADA reports

EV Sales

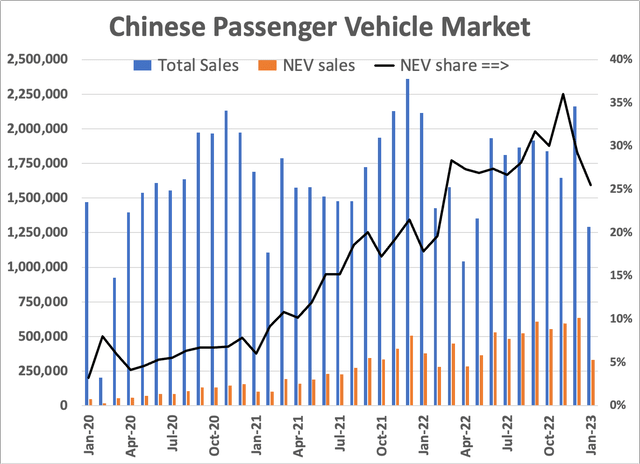

What though of NEV sales? While I otherwise ignore the differentiation, one segment was up in January, PHEV (plug-in hybrids), and by 48{515baef3fee8ea94d67a98a2b336e0215adf67d225b0e21a4f5c9b13e8fbd502}. After all, battery-only EVs don’t fit every use case, and news stories over the Chinese New Year holidays were replete with EV drivers waiting in line to plug into snow-covered chargers, as cold weather depleted their range. There weren’t many PHEV options in 2020, but then not that many EVs were sold, either. The data show the relative weight of PHEVs consistently rising, from about 1 in 8 NEVs sold in 2021Q1 to a bit over 1 in 5 in 2022Q4. That suggests an additional source of pressure on pure EV sales.

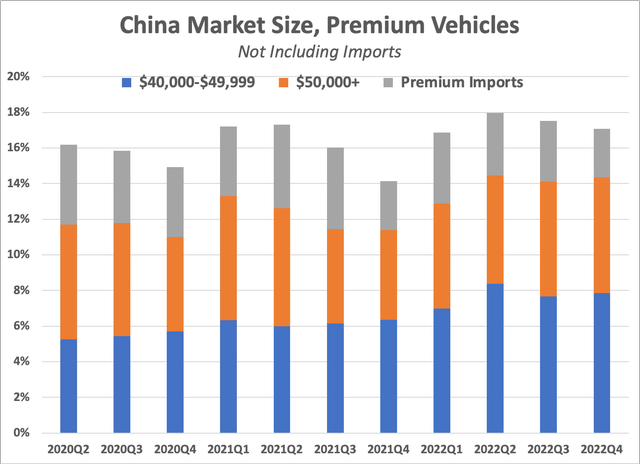

Second, the rate of diffusion of NEVs has slowed. Again, as the introduction noted, national incentives have expired and local/provincial ones haven’t increased. Historically, Shanghai has been the single biggest market; altogether, the top 10 cities account for over 1 in 3 NEVs sold (source: my compilation of monthly CPCA reports). Those markets are becoming saturated, with 40{515baef3fee8ea94d67a98a2b336e0215adf67d225b0e21a4f5c9b13e8fbd502} of sales now NEVs. They are also the wealthiest cities, and so are buying the higher-priced vehicles that NEV makers must sell to be profitable. Expanding sales requires moving into Tier 3-4 cities, but those have lower incomes, are losing populations, have governments that are in fiscal straits, and face the largest real estate losses. The latter are the dominant form of household savings, and in a down market are illiquid. (For more details on real estate, see Kenneth Rogoff and Yuanchen Yang, “A Tale of Tier 3 Cities.” IMF Working Paper 22/196, September 2022.)

Authors database, drawn from icauto.com.cn and other sources

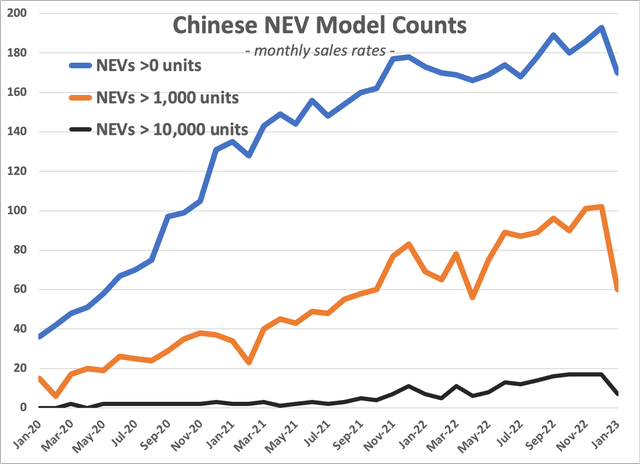

Third, there’s a price war going on. While that’s potentially good for sales volumes, it’s bad for everyone in the industry. Unfortunately for both firms and investors, competition is fierce. I track new model announcements. In 2022, my data include 232 new models and full model changes (and another 466 facelifts and minor changes). Of the new models, 70 were EVs and another 31 PHEVs. This year will see far more, with IHS anticipating 180 new EVs and PHEVs.

Authors database, drawn from icauto.com.cn and other sources

Over the course of 2023, the market will thus become more fragmented, even if some firms exit and some go out of production (as reflected in the blue line of counts of models in my database in the above graph). This should help offset the overall slowdown, as consumers will be more likely to find a model that hits their sweet spot, but it won’t help pricing. At the firm level, the net impact will depend on how many of these are new “top hats” to existing platforms that will come off an existing assembly line. For firms successfully employing a platform strategy, that will increase capacity utilization and economies of scale in component sourcing, even as it decreases sales for each individual model. Whether that will increase net profits (or slow losses) will depend on how much prices deteriorate. I don’t have access to such detailed data, nor do I have the full-time research assistant needed to pull it all together. The only analyst who seems to dive into that level of detail is Eunice Lee at Bernstein, but I have no funds invested with them so no access to those reports, which in any case I wouldn’t be able to cite.

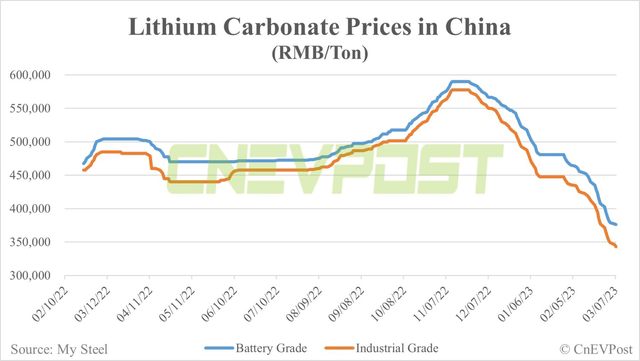

Finally, to me the most sobering item is the 50{515baef3fee8ea94d67a98a2b336e0215adf67d225b0e21a4f5c9b13e8fbd502} fall of lithium carbonate prices since December 2022. It’s not because of a large new mine entering production, or new refining capacity. Carmakers overestimated the end-of-year sales surge of consumers rushing to buy before incentives rolled off (see here), and started paring production plans. They similar underestimated the payback of lower sales in January and particularly February. Why? – because the underlying demand for BEVs is proving below consensus.

CnEVPost

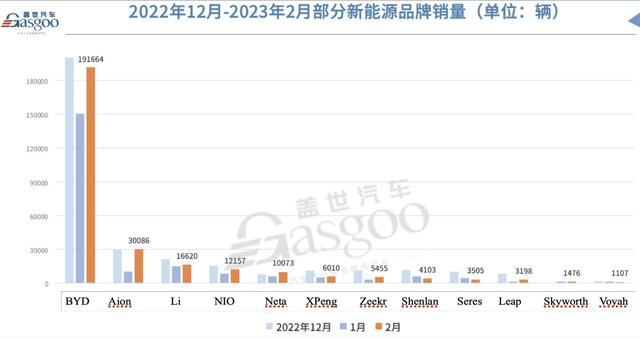

Let’s look at the performance in the major non-Tesla brands (Tesla couldn’t be included because they are slow to release domestic retail data). What the following graph illustrates is nothing short of disaster, because February sales failed in bounce back from the January holiday doldrums. The new entrants need growth to survive. Only 2 firms managed to beat December sales levels: the Guangzhou Automobile Group Co., Ltd. (GNZUF) (“GAC”) Aion brand, whose 4 models racked up sales of 270,000 units in 2022, and the small Neta (also called Hozon in some sources), with 3 models (one launched in November) and 2022 sales of 151,000. I am watching GAC, which is profitable, pays a dividend, and is trading at half of peak. Unfortunately there is no recent analysis on SA, and this article will not attempt to remedy that. Overall, though, I do not believe any of the new entrants in the graph provide “long” investment cases.

Gasgoo web site

Source: auto.gasgoo.com, to which the author appended English company names.

Tesla China

Will Tesla prove robust to these headwinds? How they fare in China in 2023 is central to their growth story and their profitability. The stock price depends on keeping both those narratives intact. Shanghai is Tesla’s largest production facility, so keeping capacity utilization high will be important to controlling costs and preserving margins. Ditto maintaining pricing.

Until we have data for 2023Q1, we will not know whether Tesla has at last dropped its pattern of end-of-quarter retail surges. Changing that habit would mean fewer exports early in a quarter and more later on, and so would leave Europe short of product, leading to a transitional quarter of poor sales. Likewise, in China operations would have to push for more sales early in the month. My own sense of organizational inertia is that such a shift could not be implemented in the space of a month or two, so again would lead to poor sales figures for the transitional quarter. I believe that Tesla management will weigh the gains in operational efficiency against the damage to the growth narrative, and choose the status quo.

That proviso aside, the data show several things.

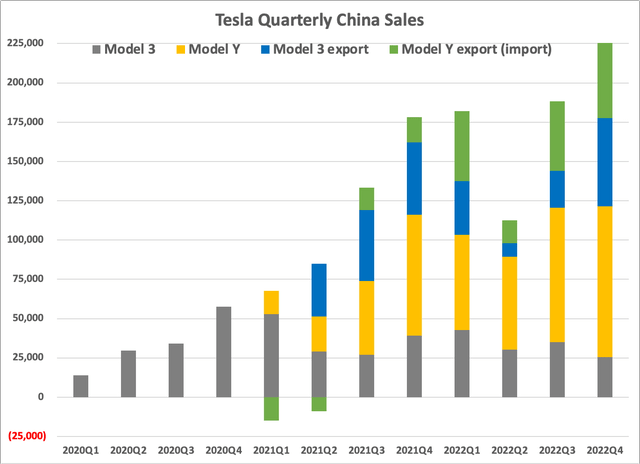

- One is Tesla’s inability to grow domestic sales of the Model 3, which in fact peaked in 2020Q4. Absent a refreshed interior and new sheet metal to update styling, sales will continue to fall under the onslaught of new models in 2023.

- The second is the success of the Model Y, which sells far better than the Model 3 ever has. With a higher selling price but non-battery production costs similar to the Model 3, it is central to Tesla’s profitability.

- The third is the dependence of Shanghai on exports, which since 2021Q2 have accounted for over a third of output (2022Q2 was an exception). Without the ability to sell into the European market, Shanghai would operate at under 70{515baef3fee8ea94d67a98a2b336e0215adf67d225b0e21a4f5c9b13e8fbd502} of capacity. Lower labor costs and component costs imply that fixed costs are a higher share. Ironically, that raises Shanghai’s breakeven point. (Thanks to Glenn Mercer for this point.)

Authors database, compiled from multiple underlying sources

All of this raises a number of questions.

- First, as Berlin ramps up, how will Shanghai keep utilization high? No other export markets (think Australia) are big enough to absorb the excess, but preliminary data for February show domestic sales below November and December 2022, while exports were over 50{515baef3fee8ea94d67a98a2b336e0215adf67d225b0e21a4f5c9b13e8fbd502} of wholesale shipments (source: CnEVPost: Tesla delivers 33,923 … exports 40,479). I follow China, not Europe, so will lean on comments in the discussion to flesh out scenarios.

- Second, Reuters reported on March 1 that Tesla will start producing a refreshed Model 3 – some new sheet metal, a modified interior – in September. However, as I argued previously on SA, the Model 3 is not in a particularly attractive segment, though sedans continue to do better in China than in North America. This should certainly stop the slide in sales, but I do not believe it will offset the limitations of the segment. Furthermore, we have no confirmation from Tesla, and every reason to believe they will miss the target date. Additionally, what will Tesla do to maintain sales of the old version after the new one has its public reveal, while will be before it is actually available for sale? Model changeovers are generally accompanied by price reductions, which with September as the date would hit both the top and bottom line in 2023Q2. Given a long history of delays, however, it’s more likely that this is a story for 2024, not this year.

- Third, will sales of the Model Y hold up? That single model is now the dominant product for Tesla in China, but it is also a stupendous cash cow, maintaining enviable volume even though it is entering its third year in the Chinese market. My sense is that there is no upside potential. Unlike the U.S., in China the share of the premium market is not expanding, and the dozen or so large, high-income cities that account for most Model Y sales are becoming saturated. Lower lithium prices will support discounting across the NEV spectrum, so will not necessarily help the Model Y. It will however allow premium EV makers with their larger batteries to lower prices more than carmakers operating in lower price brackets. With higher production volumes, and tooling costs now written off, Tesla has more room to discount than new entrants with lower volumes and brand new factories and tooling. So, I also see little downside in volume terms.

Authors database, compiled from various Chinese sources

Conclusions

There are many uncertainties going into 2023. I expect the first half of the year to see much slower growth for NEVs amidst an onslaught of new product. Sales will improve only in 2023Q4, with the normal seasonal upturn, resumed albeit slow economic growth, and lower NEV prices. New entrants in automotive face high hurdles, and I expect another one or two of the smaller NEV players to exit by year’s end, and stillbirths among those just launching their initial products. Watch for additional Chinese EV IPOs – and avoid!

Among the incumbents, GAC remains interesting, with its Aion NEV. Geely Automobile Holdings Limited (OTCPK:GELYF) has about 300,000 in NEV sales, but those are spread across multiple brands and models and corporate entities. That impedes achieving scale in production, and lowers the efficiency of its platform sharing. They nevertheless remain better than other incumbents such as Great Wall, SAIC, VW, GM, Toyota, Honda, Hyundai/Kia, FAW, Dongfeng, Changan, Chery – and on and on. China remains the world’s biggest automotive market, the biggest automotive producer, and is now a net exporter in volume terms. It is also a mature market, and that lowers its attractiveness for investors. Actions speak louder than words: I have yet to take the plunge.

Tesla remains highly profitable in its China operations, but 2023 will be challenging for the Chinese industry as a whole, and Tesla will not be exempt from those pressures. Tesla increasingly depends upon sales of a single product, the Model Y, as the Model 3 is past its prime. The Model Y continues to sell well, and is in a good segment, mid-sized SUVs. However, the premium segment is not expanding, and the steady stream of new NEV models will pressure margins for all producers. Factors such as falling lithium prices help everyone, and with competition, ultimately benefit no one (other, that is, than the final consumer).

In addition, the cash cow of Tesla Shanghai faces a major risk, its reliance on exports to Europe. No other new export markets are large enough to offset any decline there. If Tesla does launch a refreshed Model 3, it will be late in the year so the impact will be in 2024. Meanwhile, while the Cybertruck will launch in the U.S. in late 2023, it is a non-starter in China, where pickups remain utilitarian work trucks that sell in modest numbers in rural areas, and not in the major, high-income cities that comprise Tesla’s core market. Newer, less expensive models are years away and will carry smaller margins multiplied by lower prices.

In sum, Tesla has less downside than the many small players in the NEV market. In line with the NEV market as a whole, Tesla did well in 2022. It’s now payback time, and in line with the NEV market as a whole, Tesla also faces little upside in 2023. That is bad news for a growth stock.

Editor’s Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.